My hope is that this article will pique your interest and give you a sense of how you can garden with a little more ease. Who was it that said, “A garden that thrives on laziness is a great garden”? Was that just me? I’m not so sure.

Here I’m going to lay out the basics of permaculture design. Permaculture is a discipline of sustainable growing that relies heavily on the idea of a closed system, or a loop of production and reproduction where all resources are used and reused. Waste is used to fertilize new growth. Growth is used to support other growth. My suspicion is that permaculture is a good metaphor for a way to live sustainably. It’s more than just composting old plants and kitchen scraps, though.

So, what are the key elements of permaculture? To uncover this, I consulted the immanent source written by the founders of permaculture: David and Su Holmgren. Their free e-book, The Essence of Permaculture [insert link] is one of the foremost texts on the subject. They suggest there are three overarching ideas to permacultural practice:

- Earth care: rebuilding nature’s capital.

- People care: nurture self, kin, and community.

- Fair share: set limits to consumption and reproduction and redistribute surplus.

If we think about applying these ideas to humanity as a whole, we see how improvements could be made. But since that requires a lot of convincing and a complete shift of thinking and living for many, we can start on our own permaculture garden. Maybe someone will like what we’re doing and follow suit.

The Holmgrens identify twelve key principles in permaculture. They are as follows:

- Observe and interact

- Catch and store energy

- Obtain a yield

- Apply self-regulation and accept feedback

- Use and value renewable resources and services

- Produce no waste

- Design from patterns to details

- Integrate rather than segregate

- Use small and slow solutions

- Use value and diversity

- Use edges and value the marginal

- Creatively use and respond to change

One criticism of permaculture is that it is slow. Indeed, it takes time to even make it to number 3 in the list above. Permaculture requires at least one full year of observing land before planning can begin. Knowing where the sun shines through each season of the year, or how rain falls in response to trees and easements requires consistent and keen attention. So maybe that year can be accompanied by study of how to obtain a yield through the growth of ecologically sound plants, composting, and landscaping.

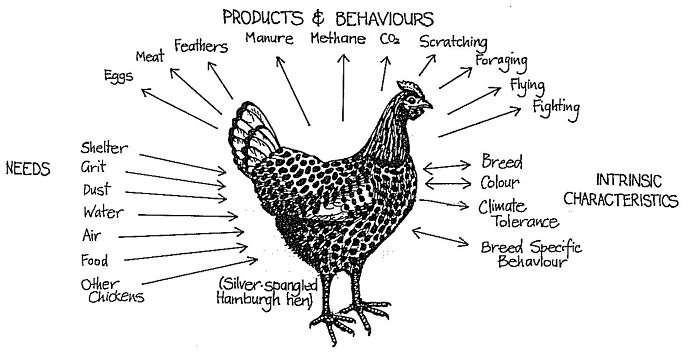

If we want to get a better sense of how each element of a permaculture setup works in a closed system, we can use this image of a chicken from Permaculture News:

Notice the arrows and how they point inward, outward, or sometimes both. The chicken illustrates how we can see inputs and outputs as an integral part of a permacultural system. Some of the best outputs chickens provide involve not only eggs, but nitrogen-fixing manure that when broken down can assist our plants with the process of rooting. Chickens are also great for pest and weed control. You can loose them in an area to remove unwanted ground cover. Although a chicken coop isn’t the nicest smelling place in the world, it’s full of cute chickens. I’m partial to them, I guess. Living side-by-side and working with animals is an essential part of permaculture. Other systems are designed around different animals: goats, rabbits, and pigs are also viable options.

This post is just the first of what will be many posts on permacultural principles and practices. It’s a subject rich in layers of information. And since permaculture isn’t a dogmatic discipline in that experimentation leads to finding new closed loops, we will touch on real-life examples that work in North Texas, where I’m situated.

Happy Gardening, Plant People!

References:

https://files.holmgren.com.au/downloads/Essence_of_Pc_EN.pdf

Recent Comments